Act Now

Empower U: Learn to Access Your Disability Rights Training on Canadian Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and its Optional Protocol (OP) training aims to increase awareness of how to address discrimination using more familiar Canadian human rights laws such as Human Rights Codes and the newer international Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). This is training for persons with disabilities by persons with disabilities. The training is part of a project funded by Employment and Social Development Canada and implemented by the Council of Canadians with Disabilities (CCD) in collaboration with Canadian Multicultural Disability Centre Inc. (CMDCI), Citizens With Disabilities – Ontario (CWDO), Manitoba League of Persons with Disabilities (MLPD) and National Educational Association of Disabled Students (NEADS). Read more.

Sign Up for our monthly digest

A monthly newsletter from CCD about what is happening in the community

Celebrating Our Accomplishments

Related Documents

March 25, 2015

Review of Extra Costs Linked to Disability

May 16, 2014

Research Report on the Québec Act to Combat Poverty and Social Exclusion, a Case of Democratic Co-construction of Public Policy

August 19, 2013

What is Happening to Disability Income Systems in Canada?

> Download PDF [2.4 MB]

November 2011

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Inclusion

- Women with Disabilities—Thirty Years

Emily A. Ternette - Women with DisAbilities: Towards Full Inclusion

Bonnie L. Brayton - A Revolution of the Mind—The Independent Living Philosophy

Traci Walters for Independent Living Canada - CACL's Deinstitutionalization Initiative: A Long Struggle

Diane Richler - Multicultural Communities Making Progress on Disability Issues

Meenu Sikand - The Impact of the Social Development Partnerships Program on the Ethnocultural Disability Communities

Dr. Zephania Matanga - Building An Inclusive Quebec

Richard Lavigne - The Disability Community and the Academic Community in Canada: We've Come a Long Way!

Michael J. Prince - Finding My Voice

Paul Young - Building an Inclusive and Accessible Canada: Inclusive Education

Bendina Miller - Reflecting on Progress Since 1981 for Post-Secondary Students With Disabilities

Frank Smith - Disability Studies

Olga Krassioukova-Enns - From Committed to Commission

Jean Beckett - Your Vote Please

Ross Eadie

- Women with Disabilities—Thirty Years

- Transport

- Moving Forward—Looking Backwards

Pat Danforth - The Development of an Accessible Urban Transportation System

Dave Martin

- Moving Forward—Looking Backwards

- Access

- Awareness Campaigns: National Access Awareness Week

Francine Arsenault - "Just A Deaf Thing"? Reflections on the Achievements of the Canadian Association of the Deaf (CAD)

Jim Roots and Henry Vlug - Access to Websites: The Golden Key to Communicating

Donna Jodhan - Stand Up (Sometimes Metaphorically) to Be Counted

Peter Hughes - The Changing Faces of Museums, Art Galleries, and Historic Properties

John Rae - The Evolution of Access

Marie White - Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs): Then and Now

Catherine Fichten - Hard of Hearing, The Invisible Disability

Doreen Gyorkos - The National Building Code over the Decades

Barry McMahon - Pathways, Potholes, Paradoxes, and Possibilities

John Rae - Inclusion by Design

Jeffrey D. Stark - Visitability—is it too much to ask?

Olga Krassioukova-Enns - Accessible Currency: A Story of Canadian Innovation and Continuous Improvement

Vangelis Nikias - Service Animal Teams: Now and In the Future

Terrance J. Green and Helen Smith - Communication: The Themes Remain the Same

Jeffrey D. Stark - Abilities Magazine

Reflecting and Inspiring Change

Raymond D. Cohen

- Awareness Campaigns: National Access Awareness Week

- Social Policy

- Special Parliamentary Committee on the Disabled and the Handicapped

Sherri Torjman - Reflections on Parliament and Disability

William R. Young - Taking Policy (or lack thereof) To Task

Traci Walters - Legislative Reforms

Michael J. Prince - Technical Advisory Committee on Tax Measures for Persons with Disabilities

Sherri Torjman - The Emergence of Individualized Funding in Manitoba—"In The Company of Friends"

Clare Simpson - Self-Managed Attendant Services Direct Funding Program—DF for short—in Ontario

Sandra Carpenter - The Disability Rights Movement in Quebec—30 years of Accomplishments

Lucie Dumais - Employment Equity and the Disability Rights Movement

Michael Huck - CPPD Reforms: An Example of Leadership Within the Civil Service

Laurie Beachell - The Registered Disability Savings Plan: A Building Block for Financial Security

Jack Styan - Supporting the Voice: The Money Trail

Laurie Beachell - Jordan's Principle

Anne Levesque - Home Support and Persons with Disabilities

Mary Ennis - In Unison: A Canadian Approach to Disability Issues

Sherri Torjman - Towards the Democratic Codevelopment of Disability Policies

Yves Vaillancourt - Nearly 30 Years of Disability Statistics

Cameron Crawford - Disability and Immigration: A Double Issue

Luciana Soave and Teresa Peñafiel - Mental Health Commission of Canada

Chris summerville

- Special Parliamentary Committee on the Disabled and the Handicapped

- Human Rights

- A Missed Wedding, a Landmark Protest and a Legal Victory

Yvonne Peters - Inclusion of Disability Rights in the Equality Rights Section of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

Jim Derksen - CCD's Role in Shaping Charter Equality

David Baker - The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: A New Era of Disability Rights

Anna MacQuarrie - Up to the Basics: The Right to Decide

Dulcie McCallum - Reflections on the Court Challenges Program of Canada

Ken Norman

- A Missed Wedding, a Landmark Protest and a Legal Victory

- International

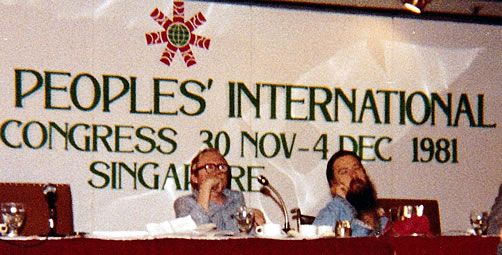

- Disability Rights: Coming of Age at the United Nations

Steve Estey - A Voice Like No Other: Ours

Diane Driedger - The Canadian Disability Rights Movement Goes International

Yutta Fricke - The Guards Allowed Us in Together

Vangelis Nikias - The Russia-Canada Exchange

Rhonda Wiebe - Nothing About Us, Without Us: Landmine Survivors Turning the Tide

Mary Reid

- Disability Rights: Coming of Age at the United Nations

Foreword

By Minister Diane Finley, HRSDC

On behalf of the Government of Canada, I am proud to offer my congratulations to the Council of Canadians with Disabilities (CCD) as you mark 30 years of achievement.

Significant process has been made in Canada over the past thirty years for those with disabilities. And it has been a collective effort by individuals, business, government and organizations like CCD.

Our legislative framework has been strengthened to ensure equality for those with disabilities, improved access to employment services and facilities—and protection against discrimination. Important pieces of legislation such the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982), the Canadian Human Rights Act (1985), and the Employment Equity Act (1995) now reflect fundamental components for those with disabilities.

CCD has been an active and influential organization over the years. That includes having played a key role in the development of the United Nations' Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which our government ratified last year. Ratification marks an important step in removing obstacles, creating opportunities and making Canada, as a whole, more inclusive.

The Government of Canada contributes to the participation of people with disabilities in society through a broad range of programs and services. In 2008, with the help of CCD, we developed the historic Registered Disability Savings Plan as a way to help people with disabilities and their families save for the future. That same year, we created the Enabling Accessibility Fund to make facilities more accessible and to date, I am proud to say that over 600 community based projects across Canada have received funding.

As demonstrated here, important work is being done at the local level. That is why we continue to work closely with the Provinces and Territories to respond to the employment needs of people with disabilities through Labour Market Agreements for Persons with Disabilities. Through programs like the Opportunities Fund, people with disabilities have the opportunity to hone their skills, prepare for the job market and contribute to their communities.

Together, we are all continuing to work towards our goal of ensuring equality for all Canadians. Evident by this publication, CCD has indeed made significant achievements on behalf of those with disabilities, along with elevating the dialogue and helping create change.

Your tireless hard work and advocacy efforts have made a marked difference and helped all Canadians to be recognized for their abilities.

Congratulations, thank you—and I wish you much continued success in the future as we work together to build a stronger Canada, for everyone.

The Honourable Diane Finley, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Human Resources and Skills Development Canada

People With Disabilities Have Transformed Canadian Society

By Tony Dolan, National Chairperson of CCD

As Canadians with disabilities we should be very proud. Our collective action over the last 30 years has transformed Canadian society and made it more inclusive and accessible. Too frequently we do not stop to reflect on what we have achieved. I know that the pace of change has been, at times, glacially slow, but when we pause to look back our record of achievements is astounding.

That is why we are producing this booklet; both to celebrate our success and to help others understand the contribution of the disability rights movement in Canada. "A Voice of Our Own" is our mantra, and that voice has been heard, respected and acted upon. We have a vision of a different kind of world. Joel Barker, an author has said "Vision without action is merely a dream. Action without vision just passes the time. Vision with action can change the world." This is what people with disabilities have done, we have changed the way in which our world sees us. Read this booklet and you see highlights of some of the fundamental changes that have come about here in Canada.

Our vision put into action has resulted in inclusion in the Charter, legislative reforms, victories in several Supreme Court decisions (Eldridge, Latimer, VIA Rail etc.), visible changes to the environment such as Closed Captioning, Braille on elevators, access to print, power doors, wheelchair ramps, low floor buses and much, much more. These changes have come about only with significant determination and effort by persons with disabilities willing to stand up for what they correctly believed they were entitled to as citizens of this country.

Changes that have come about in Canadian society have made the lives of many people with disabilities better. It is fitting and appropriate that CCD and others take time to celebrate our achievements and recognize our allies. People with disabilities and their organizations have transformed Canadian society and will continue to do so. This transformation is not simply external but also can be seen everywhere in our everyday activities. People with disabilities are present and active in our communities. There are visible symbols of our participation: ramps, curb cuts, closed captioning, accessible elevators, folks with disabilities going about their daily routine of going to school, work, shopping, theatres, day cares, parks, restaurants, etc. Yes we have much to do but those of you who are not presently disabled seem not to understand that someday you too will need similar services.

Let us celebrate our achievement whenever we can but let us also remember that after our celebration we have to get back to the work of building a more inclusive and accessible Canada.

The Disability Rights Movement: The Agent of Change for Creating a More Inclusive Canada

By Laurie Beachell, National Coordinator of CCD

I have been National Coordinator of CCD since 1984 and while I regret missing some of the exciting founding years of CCD and of the disability rights movement, I have been privileged to be a part of what has truly been a transformative journey. Throughout this journey the one thing that is clear and cannot be disputed is that the voice of Canadians with disabilities has fundamentally changed our society. People with disabilities are now seen as citizens of the diverse fabric of Canadian society, with equal rights and equal responsibilities. This societal transformation has not occurred with the speed many had hoped for but there is no denying that things are better for Canadians with disabilities today than they were 30 years ago. The central agent of these changes has been the voice of persons with disabilities and their organizations.

It is instructive and maybe important, for young people and others to remember some of what was common in the early days of the movement. There were few integrated schools; public barriers such as curbs/stairs existed everywhere; there was no public accessible transportation; access to print materials was a huge issue; housing options were few; and in many instances, people were institutionalized. People were sterilized without their consent; some were denied the right to vote; others could not marry; and many were wards of the state. Post–secondary education was rare; employment options were few; access to support services was limited; and families were expected to be the primary caregivers. There was no such thing as self-managed systems; mental health issues were stigmatized to the point of not being spoken about; human rights protections did not exist; and people with disabilities were frequently dependent upon family and the "charity" of others.

Today the expectations of Canadians with disabilities and their families are decidedly different. Canada has become more inclusive and accessible because people with disabilities have spoken out and ensured that their voices were heard in public policy debates. The voices were heard at every level of Canadian society, local, provincial, national and beyond our borders. Canadians with disabilities today seek equality not charity. They expect to attend their local school, get a job, have relationships, raise their families, and contribute to Canadian society in the same ways as non-disabled Canadians. They expect barriers to be removed and no new ones created. The changes that have come about have been made a reality because of the disability rights movement. Equally true is the fact that this could not have happened without governments' support of that movement. That support must never erode for new challenges emerge every day as our society and world find new ways of functioning and governing.

Yes, huge challenges remain; but we have come a long way. I thank CCD, its leaders, members and allies for allowing me to be part of this exciting and transformative journey. Together, all Canadians must support the disability rights movement in our country, recognizing that it is the agent of change that has created a more inclusive and accessible Canada, and it is the body that will continue to do so.

Inclusion

Women with Disabilities—Thirty Years

By Emily A. Ternette

Thirty years ago, the disability rights movement had not identified women with disabilities as having any issues specific to that population. However, in June of 1985, a Networking meeting was held in Montreal resulting in a Report: Women with Disabilities written by Jacqueline Pelletier. In this report, Pelletier indicated that violence against women with disabilities exists everywhere—in cities, rural areas, in hospitals, at home and on the streets. Women with disabilities are at greater risk of violence than other women. It was at that Networking meeting, with a handful of women listening to that Report, that DisAbled Women's Network (DAWN) Canada emerged.

Of course, prior to 1985, women with disabilities had been organizing, talking and writing about their lives. Resources for Feminist Research published an entire issue specifically on women with disabilities. In 1983, Voices From the Shadows: Women with Disabilities Speak Out by Gwyneth Matthews was published. What was and still is missing, though, is that women with disabilities are not being embraced by the mainstream women's movement—that is, there is a form of "ableism" occurring that excludes women with disabilities who want to create change for all women—both on a social and political level.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, DAWN Canada did groundbreaking work on shelters for women with disabilities with a project called Bridging the Gaps—Violence, Poverty and Housing: An Update on Non/Resources for Women with Disabilities. This project developed a tool called the National Accommodation Accessibility Survey (NAAS) which has provided important information for government to use in order to improve accessibility to women's shelters.

Also in those early years, DAWN Canada's President, Carmela Hutchison went to Ottawa to present a Brief on Economic Security to the Parliamentary Committee on the Status of Women.

In 2006, DAWN Canada, along with other community partners, held a conference that would focus on an effective strategic development that would work towards ending the isolation and exclusion of women with disabilities and help these women develop their strengths and leadership potential. The goal was to allow women with disabilities to participate in policy and social program developments aimed at improving their social conditions.

In February of 2011, DAWN Manitoba held a Healthcare Forum to determine the gaps in the healthcare system for women with disabilities in the province. They found many, and took their findings to Women's Worlds 2011.

There have been some changes for women with disabilities over the past 30 years. Employment opportunities are somewhat better and access to healthcare is improving. What is most important is that women with disabilities are more visible in the wider women's community, and they are benefiting from us being there. However, we have a long way to go.

Women with DisAbilities: Towards Full Inclusion

By Bonnie L. Brayton[1]

In the last 30 years, Canadian women with disAbilities have gone from being virtually absent in public discourse and decision-making to being recognized as experts in both the theory and practice of full inclusion. Some of the highlights of our achievements are described below.

Establishing a National Organization

In 1985 the first funded national meeting of women with disabilities was held, which led to the formation of the DisAbled Women's Network Canada in 1987. The creation of a national body controlled by, and comprised of, women with disabilities is in itself a major achievement, and DAWN Canada continues to serve as the cornerstone for the movement, leading the way in policy development, legislative change, research, and activism. In 2007, the organization rebranded itself as a bilingual organization called DAWN-RAFH Canada, strategically moved its head office to Montreal, and created a leadership position of National Executive Director.

Challenging Violence Against Women with Disabilities

Since 1989 DAWN-RAFH Canada has conducted research, developed assessment tools and training manuals and provided recommendations to government and women's groups aimed at understanding and preventing violence against disAbled women. Building on work begun in the 1990s, we conducted a follow-up survey on the accessibility of women's shelters in 2007-08. In 2008, DAWN-RAFH Canada presented at the First World Conference of Women's Shelters, where we highlighted the need for accessible women's shelters to an international audience. In January 2011, we were contracted by the Canadian Women's Foundation (CWF) to conduct a series of pan-Canadian focus groups as part of their Violence Prevention Review. We also served as key informants in this process.

Court Challenges

A number of successes for women with disAbilities have come through court challenges. Along with the Women's Legal and Education Action Fund (LEAF) and other disability organizations, including the Council of Canadians with Disabilities, DAWN-RAFH Canada has served as intervener in several such cases. Some of these include: Eldridge v. Attorney General (1997) in which deaf women were denied access to sign language interpretation while in hospital; and Barney v. Canada (2005) in which compensation was sought for Aboriginal residential school survivors subjected to multiple forms of abuse. DAWN-RAFH Canada currently has intervener status on two pending cases: L.M.P. v. L.S. (2011) in which spousal support paid to a woman with a permanent disability was rescinded based on the husband's testimony that she was capable of working outside the home; and R v. DIA (2011), in which the testimony of a woman with an intellectual disability who claimed to have been sexually assaulted was excluded because her competence to testify was successfully challenged.

A Model of Inclusion

DAWN-RAFH Canada was selected as the disability consultant to Women's Worlds 2011, an international gathering of nearly 2000 women. As a result, women with disAbilities were able to participate in all aspects of the event, and set a new standard for inclusionary practice in feminist gatherings.

A Revolution of the Mind—The Independent Living Philosophy

By Traci Walters[2] for Independent Living Canada

In the early 1980's a new perspective on disability was beginning to sweep across the country. Traditional charity and medical models of service delivery were becoming intolerable to many Canadians with disabilities. Having someone else control your life, make decisions for you, classify whether you are employable or not and decide your future was being challenged. People with disabilities, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, were demanding a power shift and were breaking away from negative stereotyping and oppression.

The Independent Living philosophy and movement were developed as a response to traditional models of service delivery. In general, society viewed disability as a deficit and that people with disabilities were considered "sick" and in need of care. Unlike traditional paradigms, the IL model encourages people with disabilities to take control over their own lives, examine options, make their own decisions, take risks, and even to make mistakes in the learning process. The IL philosophy encourages self-determination and self-actualization and promotes disability pride.

The premise of the IL philosophy has not changed over the past thirty years, only new ways in which to implement and apply it. At the heart of the IL philosophy is a change in how individuals view themselves and the society in which they live. Through the IL lens, viewing the disability as the problem is an old and outdated perspective. The barriers are not the disability—they are attitudinal and environmental. The solutions to these barriers are advocacy, peer support, self-help and barrier removal. Disability is natural and simply part of the human experience.

Allan Simpson (one of the founders of Independent Living Canada) once said, "Independent Living is not only an outcome, it is a process. When applying the IL approach, the means of addressing goals and issues were just as important as the goals themselves."

It has been demonstrated through research "that as the individual becomes empowered, participation in community life increases and in turn, the community becomes educated and significant changes occur, both within the life experiences of the individual and the community as a whole. By helping people with disabilities view themselves as valuable and contributing members of society; we have created a revolution—a revolution of the mind. There is nothing in this world more powerful than that and the many positive changes that have resulted from this."[3]

Henry Enns, Hon. Jake Epp, Allan Simpson at Funding Announced for IL Movement

CACL's Deinstitutionalization Initiative: A Long Struggle

By Diane Richler[4]

CACL's efforts to close institutions began in 1971 when Dr. Wolf Wolfensberger came to Canada as a Visiting Scholar. His task was to promote the concept of normalization—the idea that people who had an intellectual disability should be able to live lives similar to others in their communities—and didn't need institutions. Although schools and some workshops for people with intellectual disabilities existed then, the concept of providing residential services in the community was still very new and the first group homes—many of them huge by today's standard—had just begun to pop up across the country.

Many families responded very positively to the concept of community living, but others were fearful that if institutions disappeared there would not be adequate care for their family members. Most professionals were extremely critical of suggestions to dismantle the existing system. However, gradually, as more community services developed during the 70's, the tide began to turn. More families and professionals realized that people could be supported in the community. However, although the number of people entering institutions slowed down there was no major effort to close existing institutions and in the mid 80's there were at least 30,000 people with intellectual disabilities in large institutions and estimates of equal numbers in nursing homes.

In 1985, the participation of self-advocates led CACL to adopt its current name and create a Task Force to explore the implications of the name change. The result was a plan called Community Living 2000, adopted in 1986. The plan spelled out a vision for the future, which among other things, called for institutions to close.

In 1988, the federal government (which then cost-shared institutions with provincial governments under the Canada Assistance Plan) agreed in principle on the need to close institutions and made $1 million available to CACL to develop a feasible plan. Many provincial governments also agreed in principle that institutions should close, but argued that while people started to move out there would be a need for additional funds which they did not have. CACL then began working with its provincial counterparts in provinces where the numbers of people living in institutions was modest and the costs to close would not be exorbitant, and with federal officials to lobby for a transition fund to demonstrate that closing all institutions would be possible. In 1993, the federal Minister of Health and Welfare approved a budget of $15 million for a province-wide demonstration of deinstitutionalization. Initially New Brunswick was to be the demonstration province, but when they backed out, Newfoundland was ready. An agreement between the two governments and national and provincial Associations for Community Living was signed. The initiative, "The Right Future: A Future with Rights" successfully supported over 200 people to move from the Waterford Hospital to their own homes around the province. The project demonstrated that even people who had spent decades incarcerated could develop rich lives in the community. It also helped to develop a series of community services that served many people who never lived in an institution and provided valuable lessons for other jurisdictions. But while "The Right Future" was an important step on the road to complete deinstitutionalization, the journey for too many people is not over.

Multicultural Communities Making Progress on Disability Issues

By Meenu Sikand[5]

In the past thirty years, the Canadian disability rights movement has increased access to disability services, asserted legal rights through the courts and has gained some visibility on the public policy agenda. These gains have also led to positive experiences within the multicultural communities of Canada. The progress within these communities may be perceived as less significant by those who measure advancement according to traditional western values. Within ethic communities most individuals don't have rights. Hierarchy and interdependent relationships are considered a norm and achieving individual rights has a lesser importance. So the disability movement and the advancement of disability rights looks much different in ethnic communities than in its western counterpart.

Thirty years ago, people with disabilities were largely invisible in multicultural communities. They were hidden because of shame associated with having a disability, as well as the public policies and disability support system which restricted families to keep children with disabilities at home. Earlier, disability support services were only available in institutions or to adults who lived alone in apartments. Thirty years ago in Canada, disability supports were most often denied to those who preferred to stay within a family unit. Public policies were mainly designed to support individuals living in institutions or, alternatively, living alone. Such trends discriminated against ethnic communities where living with one's family was desired yet disability support services were needed due to one's disability. Disabled people wishing to live with their families were forced to live in inaccessible residences and depend on their family members for personal care and other support. Government programs were not available in family settings. Sending a loved one to an institution carried a taboo within these groups and even when they tried to access institutions, most institutions didn't accommodate the cultural needs of these families. So children and adults with disabilities in these communities were mostly hidden and supported by their family members. As a South-Asian disability rights advocate, I experienced that the disability rights movement within my community was making sure to tackle discriminatory policies that denied access to services such attendant care and home modification grants which other Canadians with disabilities were slowly beginning to enjoy in the community.

Through the application of a "diversity and inclusivity lens" some of these barriers have now been slowly removed and individuals living with their families can apply and access a variety of disability support programs within their homes in extended family units. As a result, when watching multicultural events, movies or cultural celebrations one cannot help noticing increasingly large numbers of people with disabilities participating in the life of their communities and cultural events. Many of my experiences are within the South-Asian community and I am extremely pleased to see a positive shift of attitudes towards disability. As living in large family units and relying on family members to support each other is normal, gaining autonomy and independence is desired and achieved by members of minority cultures differently than their Canadian peers.

Most South-Asians have personal relationships in dealing with disability because extended family units include children, parents, siblings, grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins. So everyone is affected by disability personally. These cultural norms created allies and champions who helped to move forward a disability agenda to tackle accessibility barriers.

During this time, I have also worked with the mainstream disability groups where a lack of minority representation continues to exist and therefore cultural issues have been largely misunderstood and ignored by Canadian disability leaders. Perhaps the recognition and inclusion of diversity in the disability movement has overlooked the cultural diversity that also exists among Canadians with disabilities.

An intersection or crossover is very much needed in the future to benefit from the strengths that each group possesses. Offering and accepting help from others is not considered offensive, or as an attack on someone's human rights, therefore the rights movement within the multicultural groups remains focused on gaining access to services. Striving for individual empowerment, autonomy and peer supports have received less attention, which were the key areas that the Canadian disability movement mainly focused on for the past thirty years.

As a Canadian immigrant, I have been very fortunate to support and lead the disability agenda for both groups. I remain optimistic that in the future diversity within the disability agenda will be acknowledged and will put an end to exclusion of people with disabilities from multicultural communities.

The Impact of the Social Development Partnerships Program on the Ethnocultural Disability Communities

By Dr. Zephania Matanga[6]

As you are undoubtedly aware, the disabled ethnocultural community is one of the most marginalized segments of our population. As a consequence, the empowerment of such communities requires a coordinated national intervention. It was through the Social Development Partnerships Program that opportunities for community participation for persons with disabilities from the ethnocultural disability were being created. Such creations of opportunities for these marginalized communities were enabled through the funding of projects specifically targeted to persons with disabilities from ethnocultural communities by the Social Development Partnerships Program. Case in point, in 2004 CMDCI had an opportunity to undertake the project: National Policies and Legal Rights: From the Disability and Multicultural Perspectives.

Through this project, experts and persons with disabilities from ethnocultural disability communities were invited from all over Canada to discuss barriers and opportunities which prevented and enabled this marginalized community to participate fully in Canadian life. One of the major outcomes of this project was putting in place initiatives that set out a strong Canadian disability strategy based on a vision of people with disabilities from ethnocultural communities as full citizens. However, CMDCI believes that these initiatives will be further strengthened by allowing the Social Development Partnerships Program to continue. This is particularly important considering that Canada is home to some 5 million visible minorities (Statistics Canada, 2009), which translates to about 600,000 of them with disabilities assuming the 12% rate used for the general population by Statistics Canada. It is important to note that this number is likely higher because most visible minorities are engaged in employment activities that increase their likelihood of acquiring disabling conditions and that this segment of the Canadian population can only be expected to grow as Canada continues to welcome new immigrants.

I would like to conclude by introducing our organization: The Canadian Multicultural Disability Centre (Inc), formerly known as The African Canadian Disability Community Association (Inc), is a national community based organization founded in 1996. It was first incorporated in Ontario in 1996 and later incorporated in Manitoba in 2002 where it is headquartered. As it relates to services, The Canadian Multicultural Disability Centre (Inc) is a community based organization whose purpose is: (1) To identify solutions and opportunities that enable persons with disabilities to participate fully in Canadian life; (2) To provide education on the role of cultural diversity in developing opportunities for persons with disabilities, particularly persons with disabilities from ethno-racial backgrounds; and (3) To enhance the skills of persons with disabilities through training programs such as health education, computer literacy and job networking.

Building An Inclusive Quebec

By Richard Lavigne[7]

Since the end of the 1970s, our country has resolutely steered towards the formal and theoretical recognition of persons with disabilities as citizens deserving the same rights as those enjoyed by the rest of the population. Since then, the Confédération des organismes des personnes handicapées du Québec (COPHAN) and its 52 regional and Quebec members have mobilized to ensure that the political, economic, community and social actors at play bring about a major and historic shift that will enable the persons we represent to take their rightful place in society.

Armed with the strong conviction that persons with disabilities can and must participate in the evolution of human activities as they have much to offer to society, COPHAN has contributed to the adoption of numerous laws and policies advocating for increased societal participation by the persons it represents. This is why, in 1978, Quebec enacted, for the first time in North America, an Act to Secure the Handicapped in the Exercise of their Rights.

Since then, COPHAN has tirelessly taken on a watchdog role and has been able to influence many governmental decisions at the Quebec, Canadian and International levels. Here are some examples:

- The implementation of a public network for rehabilitation and workforce support services;

- The implementation of an employment integration and retention program for disabilities in the workforce;

- The adoption of school integration policies;

- The complete revision, in 2004, of An Act to Secure the Handicapped in the Exercise of their Rights, aimed at ensuring their professional, social and school integration;

- The adoption of a global Quebec policy entitled À part entière, pour un véritable exercise du droit à l'égalité des personnes handicapées, aimed at ensuring greater involvement in society by persons with disabilities and their loved ones;

- The adoption in Quebec of an employment integration and retention strategy for persons with disabilities that aims to cut in half the gap in employment rate between persons with disabilities and those in the population at large without disabilities;

- The adoption of a print material and government services access policy for persons with disabilities;

- The adoption and ratification by Canada of the U.N. international Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (which Quebec adheres to).

For over ten years, a growing number of Quebec stakeholders have developed an approach based on the full and equal participation of people with disabilities in society. Quebec decision-makers increasingly adhere to the concept that, for us, the right to equality represents the application of the following principles: universal design, the duty to accommodate, access to programs and measures enjoyed by the population at large, maintenance and development of specific programs and services where necessary, and the off-setting of additional costs related to disability or handicap situations.

In short, COPHAN and its members are very proud to note that, even if much remains to be done, we can collectively build an inclusive Quebec if we all strive for it.

The Disability Community and the Academic Community in Canada: We've Come a Long Way!

By Michael J. Prince[8]

In Canada today, at the national and provincial levels, is a blend of general think tanks and specialized disability-oriented think tanks. As well, within the federal government and provincial and territorial governments, plus the university sector, are departments, agencies, advisory councils, academic programs, and research groups involved in policy-related disability research. This was not the case 30 years ago.

Production of disability knowledge is a crucial though under-resourced activity. In part, this knowledge production is an input to the other facets of the community; knowledge that supports service provision and administration, litigation or tribunal hearings, government lobbying, and cultural politics. A considerable part of disability research is in clinical and pharmaceutical trials, biomedical studies, engineering research and development, and rehabilitation treatments and protocols. As well, a growing segment of the research community is involved in the area of disability management—with links across business, government, organized labour, medicine, and the insurance industry—addressing issues of recruitment, retention, return to work, injury prevention, and workplace accommodations. Frequently, the view of disability here is in terms of health problems and impairments of the individual.

Disability studies programs in Canadian colleges and universities are of recent and growing significance. Disability studies scholars and students are producing, critiquing, and disseminating artistic, comparative, historical, and theoretical forms of knowledge on disability and normalcy. Academe evaluates policies and practices as well as assists in bringing to wider audiences the narratives of people and communities. When done in an emancipatory manner, such research not only enlightens but empowers. When done imaginatively, such work shifts the boundaries between private and public domains, making personal troubles into policy issues, drawing attention to the absolute importance of 'the family' in understanding inclusion/exclusion and citizenship. Disability studies also have an important role to play in ensuring the effective design and implementation of disability mainstreaming techniques, and their evaluation, in state institutions.

Divergent perspectives on disability circulate within Canada's policy research community. One perspective, a social model of disability (and variations on that model) emphasizes the values of equality rights and full citizenship, and usually employs a critical analysis for studying social structures and public policies. Another perspective prominent in disability research deals with functional impairments, rehabilitation, and integration. Disability management and rehabilitation therapy programs at certain universities reflect this perspective. So, too, do particular research centres on children and health services. In this orientation, people with disabilities commonly appear as individuals with special needs, facing possible risks, with official identities as program clients and care recipients.

Policy-related disability research considers public policy development and program delivery; examines the effects of policies and programs, the social environments, life transitions, and opportunity structures of persons with disabilities; and critically assesses conceptions of disability contained in laws and social practices. Intended to be usable by policy makers and practitioners, such research may serve any number of purposes: the definition and understanding of an issue; the more effective response to and management of a need or problem; the resolution or alleviation of a problem or need; the expression of voice by a group and the recognition of their experiences; the empowerment of a group through the research process; and the identification of additional lines of inquiry.

Thinking of the disability community as a knowledge production network raises implications that ought to figure in decisions about future research directions and funded projects. One such consideration centres on attracting organizations into this research community that previously have not been involved, thereby adding new players to the network, such as groups that represent employers, professionals, seniors, or unions. A second is the possibility of using the research agenda for fostering partnerships among organizations in the community and/or with actors in a related policy realm. Another is leveraging resources from the foundation sector, which, in Canada, is not a major source of funding for policy institutes and think tanks. A fourth consideration is to ensure that disability organizations of people with disabilities are adequately included in research agenda setting, resources, processes, and products of policy-related disability research. The ways of actually doing a disability knowledge strategy must involve empowering and inclusive social relations. This is absolutely crucial—otherwise, other efforts at expanding capacity could inadvertently result in crowding out and further marginalizing disability organizations within the research community.

Finding My Voice

By Paul Young[9]

I think the greatest accomplishment for persons with disabilities is finding a voice of our own and using our voice to make real change for people with disabilities. In the past, others including agencies, service providers, and the medical community spoke for us. People didn't think we had anything to say. We have been speaking out about the issues like VIA Rail, the Latimer Case, and working to close institutions for people labelled "intellectually disabled". Having our own voice has given us the vehicle to end exclusion. To be included is to be part of the whole. Life should connect you to other people. My story shows how I moved from exclusion to inclusion and how it can happen for other people.

I was labelled "mentally retarded". I attended a segregated class and a sheltered workshop. These experiences prevented me from being included. When you are excluded, you learn that you will never be able to grow. I was told I would never be able to: own a home; drive a car; get a job; love someone; be loved.

My skills and interests have given me the way to valued social roles which have led me from being excluded in a sheltered segregated environment for the "mentally retarded" to an inclusive life. I had an interest in music and radio that helped me to meet other people who were interested in music and radio. Because of this interest I met a radio announcer at a station in my hometown and he advised because I had such a keen interest in radio and music to look for a job in radio. I took his advice. I got a job at CBC Sydney as a full-time Audio Technician. I worked there for 18 years. Radio helped me grow. There were high expectations for me to do the work needed for my job. The skills I developed because of my job gave me the self-confidence to learn how to make other responsible decisions.

I have become a homeowner, a husband, learned to drive a car, got my driver's licence, and learned to play golf. I am a student, lecturer and teacher. My valued experiences have given me the opportunity to meet many people and to develop relationships with them. In June 2006, I was awarded an Honorary Degree from the Nova Scotia Community College. I was nominated and awarded my degree because of my participation in the Community College and the last thirty years of my work for fighting for equality for people. All of these life experiences and roles have led me to be a valued citizen, having personal social integration and valued social participation. I am involved with my community and I am a contributing citizen. For me, this is inclusion.

I decide to get involved with the Disability Rights movement and it helped me to find my own voice. I heard leaders talking about the issues and I got involved with a local chapter of the cross-disability group in Sydney. Ron Kanary invited me to a conference in Ottawa, where I heard Ron, Allan Simpson and Jim Derksen speaking about the lack of accessibility and inequity for persons with disabilities. Before I heard them, I was taught to feel sorry for people with disabilities. There I saw very strong men talking about the issues. I was inspired by them and decided I wanted to get involved.

It was the disability rights movement that helped me to find my voice. Because of my involvement with People First, I learned that institutions were wrong, should be closed and people should live in their community. For people who are labelled with intellectual disabilities, the closing of institutions and people being included in their communities is a major accomplishment.

My greatest advocacy accomplishment has been to get my brother, Tony, out of the institution. For 43 years, Tony lived in an institution 6 hours away from the rest of our family. After two years of advocacy, Tony came back home to Cape Breton in 2001. He now lives in a small group home and is experiencing things he never would have if he was still living in the institution.

The most important part of being included is having relationships with different people. Archbishop Desmond Tutu defines Ubuntu which best explains why relationships are important for all people: "In our African language we say, 'A person is a person through other persons.' I would not have known how to be human at all except I learned this from other human beings. We are made for a delicate network of relationships of interdependence. We are meant to complement each other. All kinds of things go horribly wrong when we break that fundamental law of our being."

Hon. Jane Stewart, Laurie Beachell, Paul Young and Jim Derksen

Building an Inclusive and Accessible Canada: Inclusive Education

By Bendina Miller[10]

I retired on July 31, 2011 following a 42 year career in education. As I reflect on the impact of inclusive education over those 42 years and specifically over the past 30 years I can speak from my experience in Western Canada, however, since education is the jurisdiction of individual Provinces and Territories there isn't a common impact across the country and Federal data doesn't give a clear picture.

My personal reflection, based on experience as a teacher and administrator at the school district and provincial levels in the four Western provinces, is that in 2011 the majority of students are receiving their education in inclusive classrooms in their neighborhood schools for their elementary years and receive their education through a combination of inclusive classrooms and specialized subjects in secondary schools. Thirty years ago it was more common for students to be registered in special classes away from their neighborhood schools and their neighborhood peers. Thirty years ago it was also more common that students in secondary schools were registered in 'Resource Rooms' where they had very little interaction, even on a social basis, with their nondisabled peers. Thirty years ago segregated schools were accepted by many jurisdictions as appropriate settings for students with disabilities, however, that would be a rare circumstance in 2011.

Children who are educated in an inclusive setting have a social advantage and a positive impact on their health. Students who become friends in their elementary schools and neighborhoods are more likely to be friends, advocate for and support each other through secondary school and into adulthood. The impact that inclusive education has on building safe and supportive communities means that all citizens are able to live in a manner which is more conducive to success. In a recent document 'Inclusive Education Knowledge Exchange Initiative: An Analysis of the Statistics Canada Participation and Activity Limitation Survey' Dr. Vianne Timmons and Maryan Wagner report that parents whose children are educated in inclusive settings say that their children are healthier, enjoy going to school, make good progress in school and interact well with their peers.

Inclusive employment and inclusive postsecondary options have been developed over the past 30 years with students who have graduated from inclusive secondary schools being successful in these settings rather than being placed in segregated day programs. The skills and confidence developed through inclusive education contributes to the success of inclusive adult environments which are enabled by both employers and post-secondary staff who have grown up in inclusive schools and by students with disabilities who graduate with an expectation of continued inclusion. This powerful reality has developed in a limited way over the past 30 years with the expectation that inclusive employment and post-secondary education will become more commonplace for students as they graduate from inclusive secondary schools.

As I anticipate the future I am optimistic that CACL's vision, 'diversity includes', will be a reality for all. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, ratified by Canada in March 2010, sets out an agreement that all Provinces, Territories and the Federal government support articles which provide for an inclusive society, including Article 24 Education. Thirty years later we are able to learn in a collaborative manner which engages us in thinking and considering practice to become more honouring of the learning needs of all students. I urge you to access Inclusiveeducation.ca as a way of staying connected through powerful input of parents and practitioners who share a commitment to inclusion.

Reflecting on Progress Since 1981 for Post-Secondary Students With Disabilities

By Frank Smith[11]

I'm honoured to have been asked to contribute to this book that the CCD is putting together. I'll be offering some reflections on advances and changes that have taken place for post-secondary students with disabilities since 1981. I've been working as the National Coordinator of the National Educational Association of Disabled students (NEADS) for 25 years, so there's a lot to reflect upon over the period that I've been working actively on the issues. But let's start with an observation based on my own university experience. Way back in 1981, I was a first year student in the Journalism program at Carleton University in Ottawa and I had a friend who was blind, a year ahead of me, in the same program. I don't know how he completed what was a very demanding journalism course load and media assignments, given almost insurmountable obstacles in his path. This was long before the Internet, of course, email and adaptive technologies that students take for granted now. And this friend didn't even have a computer through much of his studies. He relied on Braille and 4-track tape recordings of his class materials. And I know that his books on tape were almost always weeks late.

Fast forward 30 years and this same student would have a computer, access to a range of adaptive technologies, books available in accessible electronic formats, and a wealth of materials online. Things aren't perfect now by any means, but great strides have been made for college and university students with all types of disabilities. NEADS now has some 220 post-secondary institutions that have designated disability services offices in a fully accessible, searchable database on our website. These centres are staffed with experienced personnel that can assist with individualized accommodations to students with disabilities so they can be successful in their studies. And the disability service providers have organized themselves in a national group—along with some like-minded provincial groups—that attempts to ensure a standard level of professional service delivery and support across the country.

Universities and colleges across Canada—aided with provincial and federal funding—are allocating significant resources in their budgets to support disability services and to provide adaptive equipment in libraries and other places on campuses. In many parts of the country—Ontario with the AODA is a prime example—schools are having to report to their provincial governments on progress they are making to improve physical access, provide services, accommodations and badly needed adaptive hardware and software. With greater awareness comes greater acceptance as well. For example, professors and teachers are much more willing to provide accommodations like extra time for exams and assignments and private areas to do exams than they were years ago. The student population generally considers classmates with disabilities as peers, part of the fabric of the campus community and there is less discrimination in universities and colleges than there used to be.

Another big change that I've seen is in the level of involvement of students with disabilities on their campuses, in working with key players to ensure that all aspects of accessibility and services to students with disabilities are being met. Many schools are asking students with disabilities to sit on influential committees that are making decisions on key campus issues including: new construction, methods of delivery of course materials in the classroom, the purchase of new technologies, and the development or modification of disability policy statements. A growing number of students' unions/associations are supporting the establishment of organizations of students with disabilities, with office space for their activities. These centres are being set up and supported along with the centres of other equity seeking groups: women, international students, first nations students and GLBTQ students. Students with disabilities are now more likely to compete for positions on their student governments, which is hugely important.

I've also seen great advances in the level and type of financial assistance available to students with disabilities. Most students in college or university study are familiar with the Canada Student Loans Program offered through the federal government. Now, in addition to regular student loans that most students can access, there are Canada Student Grants for students with permanent disabilities that cover a range of equipment and accommodations costs. This can amount to thousands of dollars in grant funding over a student's years of study. And now there is an upfront grant of up $2,000 per year that disabled students can access to cover costs like tuition and books. If you factor in provincial grant and loan funding programs, students with disabilities and their families are in a much better position to support the costs of their education and any additional disability-related expenses, than they were 25 years ago. But of course tuition fees and the cost of living continue to increase at an alarming rate, so access to adequate funding will continue to be a concern for many disabled students. And there will always be added concerns for students who have higher costs, such as deaf students who need sign language interpreters.

Also on the subject of funding, I have noticed that an increasing number of colleges, universities, private sector funders and non-governmental organizations are offering scholarships, awards and bursaries designated for students with disabilities. NEADS has catalogued hundreds of these funding sources in a fully accessible, infinitely searchable financial aid portal that we launched about a year ago: www.disabilityawards.ca. There was little of this kind of support years ago and there certainly wasn't one place where you could access the details on disability scholarship programs.

The other significant change that I'm seeing, which is critical, is an increased interest in academic programming that addresses disability and human rights with a disability lens. Disability Studies programs are emerging all over North America on university campuses. There are many such programs in Canada now, most notably at York University, Ryerson and the University of Manitoba. As the area of disability studies has become a serious area of academic research, the graduates of these programs move into society to make substantive changes at all levels for persons with disabilities.

While improvements have been made and great strides have been taken since 1981, there are still areas that cause us considerable concern. In our office we are hearing from an increasing number of students who have considerable challenges because of chronic health conditions— often autoimmune related disabilities—that can cause interruptions in studies for periods of time and difficulties addressing changing accommodations requirements in the classroom. Sometimes these students have to drop out of school altogether because they can't cope with the stresses of school and illness. Students with mental health conditions face great barriers because of the invisible nature of their disabilities. And it seems that the proportion of students battling mental health problems is rising dramatically.

So, in summary, big things have happened in the last 25 years and many advances have taken place. But we can't be complacent because there are always obstacles to learning to overcome and technology, which can be the great equalizer in the classroom, does not solve every access problem. I encourage students with disabilities to visit our website or contact our office directly for information, advise or assistance.

Disability Studies

By Olga Krassioukova-Enns[12]

Disability Studies (DS) has emerged as a discipline within the contexts of the disability rights and independent living movements, which have advocated for civil rights and self-determination since the 1970s. These movements have achieved significant policy change on behalf of the persons with disabilities in Canada and the United States. By bringing together academics and disability community advocates who shared common concerns the movements have also assisted with the continued development of DS. DS has moved disability from medical and rehabilitation domains into the political and social realms. It has resulted in the development of a 'disability framework' which examines the social, political and economic forces that have marginalized and oppressed persons with disabilities for centuries, just as feminist and other frameworks have been developed to address the historic and systemic disadvantages of women, children, poor and other marginalized (or minority) groups. While DS recognizes physical, mental and other differences amongst individuals, this perspective stresses the importance of proper interpretation of such differences.

In Canada, part of the DS history began in Winnipeg, when in the 1990's the late Henry Enns (Co-founder and first Executive Director of the Canadian Centre on Disability Studies) and other disability community activists began to lobby the University of Manitoba to develop a Disability Studies program. In May 1998, CCDS hosted the first Symposium on Disability Studies to continue these discussions. Contributors from Manitoba, Alberta, Quebec, Ontario and Chicago, addressed the symposium participants who represented disability organizations and universities across Canada. That working meeting enabled CCDS to consult with members of other academic institutions who were in a position to advise on, and assist with, the implementation of the interdisciplinary Master's degree program. The nature of CCDS's vision was the development of a Master's program that would be meaningful to people with disabilities, have high academic standards and integrity, provide disability knowledge and critical thinking to future professionals, and serve to facilitate the full inclusion and participation of persons with disabilities. Many consumer organizations have agreed on the need for a Disability Studies program that emphasized cultural and social definitions of disability, while adopting an interdisciplinary approach.

Growth of Disability Studies in Canada:

1999—First undergraduate disability studies program at the Ryerson University's School of Disability Studies

2002—First Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Disability Studies at the University of Manitoba

2004—Canadian Disability Studies Association

2007—First PhD program in Critical Disability Studies at the York University

2011—10 Disability Studies Program at postsecondary institutions

Dream (by 2015)—Every postsecondary institution in Canada will have an interdisciplinary disability studies program at the graduate level.

Disability Studies helps to change the way society perceives and responds to disability. It can deepen our understanding of the disability rights movement and generate and/or disseminate knowledge that can enhance the process of social change. However, Disability Studies also has implications that reach beyond people with disabilities.

Disability Studies helps to shed light on broad societal issues, challenge societal thinking regarding the ways it meets the needs of all its citizens, the processes of adequate resource distribution, etc. By encouraging the value of diversity, it can help create a more just and responsive society.

From Committed to Commission

By Jean Beckett[13]

This is a story about a journey of many years taken together by many people. I was not present for the entire journey so I will give you a little history as I have been told and then speak of my personal journey.

When I was young, the women in my family did home care. I loved helping the women care for everybody so I dreamed of becoming a doctor. When I was nine, my dad died and mom started drinking. Seven years later she died and I became a homeless orphan. The trauma of my childhood had left me struggling with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Agoraphobia with Depression to add to my asthma and severe allergies.

Meanwhile, a group of Viet Nam veterans decided being placed in wheelchairs and confined to VA hospitals was not acceptable. They wanted to pick up their lives where they left off and live active lives in an inclusive society. The Independent Living Philosophy was born. It became a movement founded on empowerment, inclusivity, and a barrier-free society. They fought for and won the Americans with Disabilities Act which compels public places, goods and services to be fully accessible.

In the early seventies, people with disabilities (PWDs) in Canada began a movement of their own and Independent Living Canada was born. Resource centres that practiced the independent living philosophy and use a peer support model began to open up across Canada. They are non-profit grassroots organizations with Boards of Directors, staff and membership who are primarily PWD's. They advocate for inclusion and an end to discrimination and stigma.

In the early 1990's I attended a training course for upgrading from my Personal Service Worker (PSW) and met the instructor Kathie Horne. The minute she entered the room I was fascinated by this woman who obviously had a fairly severe form of Cerebral Palsy. Her body was twisted, her speech quite stilted and her eyes crossed. I saw through all of this and was completely gob smacked by her intelligence, humor, and courage. Her beautiful brown eyes sparkled and danced with passion when she spoke. She was positively fearless! She spoke of the Independent Living movement and her desire to start an IL centre in our small Ontario town.

We became immediate friends and partners in the work. We organized a group of PWDs and began lobbying for access. For five years we worked with the community, governments, and funding bodies to further our cause. We established an Access Awareness Committee and did public information presentations and events. Finally, we opened the doors to RISE Resource Centre for Independent Living and stepped up our advocacy work. We joined hundreds of PWDs across Ontario to become the Ontarians with Disabilities Act Committee. This lobbying group focussed on writing the Ontarians with Disabilities Act (ODA). The government wrote an ODA of their own that was soon struck down and replaced by the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA).

Meanwhile, back at the Independent Living centre, we were developing the Direct Funding Program for Self-managed Attendant Care. Next, we trained our staff and volunteers in Universal Design and went out doing accessibility audits for builders, architects, and organizations and promoting the newly revised accessibility standards in the Ontario Building Code. We continued to lobby for inclusion and for improvements in goods and services. As changes were achieved and implemented, we quickly developed activities to educate people and promote the changes, as we recently did by providing workshops about the new Registered Disability Savings Plan. This exciting program has been implemented by the Federal government to proactively empower PWDs to save for their later years without jeopardizing any income security program they may be currently receiving.

Then, in 1999, I joined a group of individuals who were persons living with mental health issues. Identifying themselves as Consumer Survivors, they had been mirroring our work within the mental health system. They were also creating a movement and fighting for power and control over their own lives. They use the catchphrase "Nothing about us without us." Since I identified as being a person with lived experience, I joined them to partner in their work.

Our biggest success so far is a network of consumer survivor initiatives that are peer support organizations similar to the IL centres. With research showing that peer support is Best Practices in the mental health field, we continue to lobby the Ontario government to strengthen these groups and enhance their programming.

Meanwhile, the federal government has responded by creating the Mental Health Commission of Canada whose mission is "to promote mental health in Canada, and work with stakeholders to change the attitudes of Canadians toward mental health problems, and to improve services and support". To achieve that end, they have been involved in activities ranging from the development of a Knowledge Exchange Centre, a housing project, a peer project, and programming designed to foster partnerships and reduce stigma through education and understanding. They are developing a national mental health strategy and spearheading collaborations involving persons with lived experience, family members, professionals, the corporate world and multi-levels of government.

It has been a long road travelled by many thousands of people united for a cause and we have come a long way.

It is just the beginning.

Your Vote Please

By Ross Eadie[14]

Four days in April, 1992 sent me on a path leading to a successful election to Winnipeg City Council in October, 2010. During an Independence '92 plenary session that included Henry Enns and Allan Simpson, people from around the world heard about great success in Independent Living advocacy efforts in the industrial world, but the following words rang out to me: We have yet to elect persons with disabilities into governments at all levels where we can influence decisions from within. Imagine if people with disabilities had been sitting in cabinet while a new Charter of Rights and Freedoms was discussed in the context of what it should cover. Including the rights of persons with disabilities in the Charter would have started at the beginning, instead of requiring a huge effort to include them near the end of the process.

Advocacy efforts drove me to become a politician at the municipal level. The city comes into one's life more often than the other levels. But, I have campaigned at the federal, provincial and school board levels, which involve education, health, housing and income. All four of these issues are at the top of the list to improve life for persons with disabilities and those without disabilities.

We have had some success in electing persons with disabilities in Canada. At least two persons who are blind have been school board trustees in the prairies. A woman with a disability has been the mayor of a small city, and a man using a wheelchair became the mayor of Vancouver. A person who is deaf became a member of the Ontario government, and a woman with a disability has become the Minister of Labour in Manitoba. A man who experiences quadriplegia and a woman who experiences paraplegia have become Members of Parliament. I am sure there are more examples, but there needs to be many more to be representative of our society.

One interesting point must be made in terms of electoral progress in Canada. None of these people ran on the issues of people with disabilities. We were part of campaigns about issues everyone in society is concerned about. Each of us has political ideals from our political parties. We are women and men; fathers and mothers; single and married; gay and lesbian; and of many ethnic backgrounds. It can be difficult to hear from voters who want to make your disability an issue, but I truly believe the huge effort in educating the public over the past 30 years has made this a very small number of voters.

It is my belief that much more success will come in electing persons with disabilities in the next decade. I am not sure about where my political career will culminate before retirement, but I do know nobody will be asking me to wait at the door while they get money to donate to "the blind guyˮ. They know it is "your vote please."

Transport

Moving Forward—Looking Backwards

By Pat Danforth[15]

In 1981 a wheelchair user could not take the train or bus from the West Coast to the East Coast. In 2011 a wheelchair user cannot take the train or bus from the East Coast to the West Coast. Individuals with sensory disabilities still cannot travel with confidence that they will be able to see or hear what is going on. Has anything changed? Have we progressed? Yes things have changed and yes we have progressed but in a piecemeal, scattered way that often frustrates the traveller with a disability but our goal of full participation and equality is slowly taking shape.

Looking back it is hard to believe that 30 years ago many of us living with disabilities were being denied basic transportation. Canadians with disabilities were denied the right to participate in our communities and country because of manmade barriers. The majority of fixed route transportation systems—road, rail, or air—were inaccessible! Change came because locally we, people with disabilities, participated in and advocated for the development of parallel transit services and then conventional transportation to meet the needs of folks who do not climb stairs and now we champion better access for people with sensory disabilities. Nationally we have won great victories by voicing our concerns and championing for change. In the late 1980's we helped put in place the Canadian Transportation Act. It governs air, rail and interprovincial ferries. The Act entrenched the concept of equal access by recognising obstacles to our mobility, and includes investigating complaints, developing regulations plus codes of practise and conducting compliance reviews.

Despite the provinces and municipalities being responsible for urban transportation and the federal government responsible for interprovincial and international transportation, we struggled and eventually established two significant precedents. VIA Rail's purchase of inaccessible rail cars in 2000 was confirmed as discrimination and those cars were ordered to be retrofitted. The process took 7 years but the Supreme Court clearly said "no new barriers" when it comes to transportation and travelers with disabilities. One person—one fare recognised individuals will not be charged more than one fare if they need help in flight for personal care or safety and/or because of their size needs more than one seat. It only applies in Canada and to the major airlines but it is making a huge difference to individuals who need this. These wins help us move towards a transportation system that is consistent, seamless and useable by all including people living with a disability.

We have made tremendous progress over the last 30 years but we still have a ways to go to assure our systems of transportation will be inclusive. Our challenges include travel information being accessible for people with sensory disabilities, real time information available visually and audibly, tactile and audible signage systems, new technology that is useable, and most important—no new barriers!

We intend to meet the challenges head on.

Pat Danforth at Supreme Court of Canada

The Development of an Accessible Urban Transportation System

By Dave Martin[16]

I will never forget the day about seven years ago when I rolled up to my father's house on the west side of Winnipeg for an unexpected visit. He was outside cutting the grass as I came up the driveway in my electric wheelchair.

He didn't notice I was there until I said, "Hey, you missed a spot."

He spun around with a puzzled look, as if he was seeing a mirage. Looking around for a van or Handi-Transit vehicle that might have dropped me off, he was confused because there were none to be seen.

"How in the world did you get here?" he asked.

"I took the regular bus for the first time." I answered with a grin.

In many ways, my bus ride that day and surprise visit to my dad's was the perfect tribute to years of work by countless people from Winnipeg's disability community. Just a few short decades ago, many people with mobility disabilities were often stuck in their homes, because they had no accessible transportation available to them. Other times they had no option but to pay expensive fares to specialized wheelchair transportation companies, just so they could get somewhere they wanted to go.

Then, in the 1970s, people with disabilities started to learn from groups representing the rights of women and visible minorities. Many of their concerns were similar to those of people with disabilities who were just starting to fight for access to a society that had ignored their needs.

Access to public transportation was one of the first priorities of the new disability rights movement. People with mobility disabilities in particular were tired of not being able to use a transit system they were paying for with their tax dollars. Organizations like the Manitoba League of the Physically Handicapped (now Manitoba League of Persons with Disabilities) led the fight at Winnipeg's City Hall to convince civic leaders that people with disabilities had a right to use public transit.

This advocacy eventually saw the introduction of Handi-Transit as a parallel public transportation service operated by the City with fares equal to those paid by regular transit riders. It was a significant liberator for many people with mobility disabilities as it allowed them to get out and start participating in society to a much greater extent.